Tuesday, December 17, 2024

Prokofiev, Romeo y Julieta en ADDA Alicante

ADDA·SIMFÒNICA ALICANTE

JOSEP VICENT, director titular

ASUN NOALES, dirección escénica y coreografía

Rosanna Freda, asistente de coreografía

Joaquín Hernández, Diseño Iluminación

Luis Crespo, Diseño espacio escénico

Ana Estéban, Vestuario

Federica Fasano, Investigación

Germán Antón, Fotografía

Bailarines: Deivid Barrera, Rosanna Freda, Diana Grytsailo, Iván

Merino, Alice Pieri,

Laura Martín, Joel Mesa Gutiérrez, Salvador Rocher, Theo Vanpop, Jennifer

Wallen,

Samuel Olariaga, Araitz Lasa

What can surprise

in a performance of music that is almost known by heart, providing a scenario

for a ballet whose story one has heard and seen performed countless times? The

answer is just about everything. A story is as old as its current telling, if

the tellers have told it their way. This was very much the case last night in

Alicante when the ADDA Orchestra under Josep Vicent played Prokofiev’s Romeo

and Juliet to the choreography of Asun Noales.

One always needs

to be reminded of the power of human imagination, and this performance will

live log in the memory. Here there were no sumptuous costumes, no monumental

sets. Staging was accomplished with a few cubes that could serve as seats,

walls or plinths, and a pair of steel scaffolds that had vegetation on one

side. These could be rotated to present a garden, a balcony or a tomb. Costumes

were minimal, with the feuding Montagues and Capulets needing no obvious

uniforms to identify their allegiance.

But what was on

display was raw emotion, vividly portrayed by a quite excellent choreography.

There was not a single gesture in the audience’s view merely for the sake of

the gesture. Nothing was purely technical. Everything meant something.

The audience was

left in no doubt about the sexual nature of Romeo and Juliet’s

mutual attraction. And the fight scenes were utterly convincing, despite the

fact that no weapons were ever visible.

Perhaps the most

surprising aspect of the whole evening was the portrayal of Father Lawrence. Prokofiev’s

sensuous music was the raw material, but the choreography depicted a character

that was sinister, clearly devout and all too willing to help, but also someone

who wished to envelop and control. It was a depiction close to witchcraft, but

probably got closer to a medieval mind’s interpretation of religion, with its

capacity to deliver eternal damnation and suffering than any other I have seen.

Rosanna Freda and

Salvador Rocher in the principal roles were hardly off stage, but other

performances were also superb, not least the Mercutio, the Tibalt and the Nurse.

And everything was delivered by a dozen dancers.

This was a

minimalist production with wholly modern choreography, but the humanity that

was depicted was direct, very moving, and communicated so vividly that it rendered

considerations of “style” simply irrelevant.

Wednesday, December 4, 2024

Monday, December 2, 2024

Orfeón Donostiarra, ADDA, Josep Vicent serve two staples of twentieth century music in Alicante - Orff's Carmina Burana and Ravel's Daphnis and Chloe

How does one review a work in which one section is so well-known that it is perhaps better known as an aftershave advert on television than is a piece of music? How might one describe again an experience that has already been played through on multiple occasions? Here is the problem for this reviewer of last night’s concert in Aliante, in which the ADDA orchestra under Josep Vicent alongside Orfeón Donostiarra presented two utterly familiar masterpieces of twentieth century music. Let’s start with the aftershave

Given the opening paragraph, “old spice” is perhaps a good label from which to start. Carl Orff’s Carmina Burana is perhaps an example of old spice. Since it’s rapturous reception in Nazi Germany in 1937, it has continued to spice up concert programs in more ways than one. The composer chose to set these medieval poems, not only because they were interesting in themselves, but also because they were rather iconoclastic. Although written by clerics and monks several hundred years ago, they are at least tongue-in-cheek, anti-clerical, and anti-church. They are also bawdy and celebrate sex and drinking. Rabelaisian might be a relevant word.

But they do their iconoclastic work in the conventional format of a cantata with soloists, though only three of these, not four. One of them, usually sung by a tenor, has the utterly thankless task of playing a roasting swan with a skewer inserted in such a way that it changes the voice to falsetto. Though food seems to be the preoccupation, one is reminded of the medieval church’s propensity for making bonfires. The part was convincing sung by Rafael Quirant, who is a countertenor, who inspired genuine pathos amid the implied mirth.

Milan Perišić’s baritone was superb throughout. This is the meat of the soloists’ contribution, and his approach was genuinely and convincingly operatic. He generated superb dynamic contrasts at times and was thoroughly in control throughout. The soprano sung by Sabrina Gárdez, had two major contributions towards the end, and during the second, the voice has to live alone amongst those assembled vast forces. It has to modally meander its way through a solo without accompaniment, and then meander back again to finish in the right place. Many do not succeed, but Sabrina Gárdez did. During this sequence, one reflects how rarely in this work anyone sings anything without unison accompaniment.

And, speaking of singing, Orfeón Donostiarra visiting Aliante again did a wonderful job on the text. Their collective subtlety of expression brought out what was in the work to express. Much of this choral writing seems to have the character of plain chant with rhythm, so often there simply isn’t the opportunity to show off harmonic complexity. Rhythmically, it’s a very different story and our choir was perfect.

So what does one do musically with it? The quiet sections have to be quiet and lyrical, while the fireworks need to be loud, spectacular and perhaps augmented by both speed and volume. Josep Vicent chose to mix in both at the end of tutti phrases and everything worked beautifully.

The other part of the evening was devoted to another resident of the concert hall repertoire, the second suite of Daphne and Chloe by Ravel. There is nothing literal about this music. Everything is mere suggestion, an expression of whatever internal reality or myth Maurice Ravel was wont to experience. As ever with Ravel, it is hard to pin this music down. It has to be experienced live and its effect, though lasting, even permanent, does not prompt the retention of earworms. A wordless chorus does much more than add emphasis and volume to the beginning and end. In the dawn sequence, especially, they add harmonic texture and colour.

What is utterly

fascinating to see how the composer’s mind worked. In the opening dawn

sequence, the violins are playing a repeated, barely audible arpeggio, which

suggests darting insects, barely visible through the mist. This is music of

truly sophisticated complexity, containing sound that has to be experienced and

cannot be hummed, unlike Carl Orff’s masterpiece, which in comparison, does to

the audience what the skewer does to the swan.

Wednesday, November 27, 2024

Saturday, November 16, 2024

Helsinki Philharmonic under Saraste play a Sibelius programme

Jukka-Pekka Saraste conducted the Helsinki Philharmonic orchestra in a program devoted to the music of Sibelius. Now a Finnish conductor with a Finnish orchestra playing Finnish music might sound like it could turn out to be a cliché. But these people know precisely what they are doing with their national composer. Clearly, the Helsinki Orchestra plays a lot of Sibelius, but they also clearly never tire of the task.

The concert started with a work not published in the program. The previous concert had been cancelled in the aftermath of the devastating floods that had hit the Valencian region. As a mark of respect for those who have suffered, the orchestra opened with the Valse Triste of Sibelius. It was a gesture appreciated by the audience.

The first half of the concert then got underway with Jan Söderblom, the Helsinki Philharmonic leader playing the First Serenade for violin and orchestra, Opus 69a. This is a thoroughly understated work. The Second Serenade, more substantial and more musically interesting came third on the program with Jan Söderblom again as soloist.

In between, the orchestra’s principal flute, Niamh McKenna, was soloist in the Nocturne No.3 from Sibelius’s incidental music to Belshazzar’s Feast. So it was with these three short pieces, featuring solo violin, flute, and then violin again that the concert started. If I have a criticism, which I accept is the level of nitpicking, I would suggest that these three pieces should have been presented with the flute first or last, allowing the two serenades to be played back-to-back. It was in this form that the Helsinki orchestra premiered in 1915, a concert which also featured the original version of the fifth symphony.

The performance of Finlandia that followed saw several extra musicians take to the stage and the familiar cords did ring out. Finlandia is a thoroughly moving experience and no matter how many times it is played, it always has a rousing effect on an audience. This was no exception.

The second half was taken with a performance of the Fifth Symphony, though in its revised version, not the original of 1915, which is never now played. And the fifth is perhaps the composer’s most popular work, alongside the Violin Concerto. With such a well-known work, it would be easy to fall into the trap of mouthing platitudes, but this performance was anything but that. The music was fresh, as fresh as Sibelius himself would have wanted when he said that whereas modern composers were offering up cocktails, he only wanted fresh spring water. The music was both clear and refreshing.

There was also an encore, the Alla Marcha from the Karelia, which needed even more musicians on stage

Friday, November 8, 2024

Shunta Morimoto at the Denia International Piano Festival in Bach, Chopin and Liszt

I don’t normally write detailed reviews of chamber music concerts. It’s not because they often aren’t memorable, it’s just that I tend to go to so many of them, it’s often hard to keep up with the writing! This lack of motivation to put pen paper is especially marked when the repertoire on offer is very much standard, comprising often performed works that frankly I have heard many times. It’s not that familiarity breeds contempt. It’s just that what does one say about another fairly standard performance of a standard work, albeit that both the work and the performance are superb? Nearly all the performances I have heard over the years are wholly competent, with one or two exceptions, but it becomes hard to say anything new about them. So what is it about a concert that featured J. S. Bach’s French Suite No. 6 BWV 817, Chopin’s Opus 28 Preludes and Liszt’s Dante Sonata that has provoked me to write? Answer: the performer and the performance. Both were outstanding.

Shunta Morimoto is a young Japanese pianist. He was 19 when he won the Concurso de Piano Gonzalo Soriano in Alicante in April 2024. The competition is organized by Ars Alta Cultural in conjunction with Conservatorio Profesional de Música, Guitarrista José Tomás and this year there were over 100 entrants, with half of them competing in level D, the section for adults, whose age rage was from 18 to 32. Shunta Morimoto, therefore, was at the younger end of the range, and he was the youngest of the finalists. I have been listening to music intently for about 60 years. But I knew from the moment Shunta Morimoto depressed a key in that room in April that he would win the competition and, furthermore, that I was about to witness something wholly special. Put simply, Shunta Morimoto is a genius.

Part of the prize for winning the Gonzalo Soriano competition was to appear in the Ars Alta Cultural concert series in Denia at the end of 2024 and that concert, part of the Denia International Piano Festival, was last night. Shunta Morimoto offered the program mentioned above and, for perhaps the first time in thousands of concerts and recitals that I have attended, I can report that not one of the 110 or so people in the audience made a single sound, apart from applause, of course, throughout the one and a half hours of music. There was no interval, but amongst the audience, silence ruled, so utterly wrapt was everyone in what they heard.

It is hard to describe in words what is so compelling about this young man’s playing. The moment you hear the music, it is obvious, but written words have to be read, not heard. Many pianists use bravura, strength and volume to impress. Many play as fast as possible. Shunta Morimoto can offer bravura, the spectacular and the speedy. But above all what he can do is communicate via the music and it is this speaking, apparently directly to an audience without the need of words that is utterly captivating, even arresting.

Every phrase of every piece he played last night was shaped, thought through to make musical sense. At times, he played so softly the music was barely audible, but every note was there, every gesture was clear, every phrase fit perfectly with the musical argument he presented. Even the silences he interspersed for effect were listened to intently by a thoroughly captivated audience.

Chopin’s Opus 28 Preludes, perhaps, was never intended to be played as a single work. But in the right hands, even a composer’s lack of vision can be straightened. I am reminded of a performance about 30 years ago when Murray McLachlan played all the Etudes of Chopin end to end, Opus 25 followed by Opus 10. He was clear that it would not the other way round. I have never forgotten that performance on a baby grand Kawai in a Brunei Hotel. Last night, Shunta Morimoto knew that the Opus 28 Preludes could be played as a single work, and he was right. He succeeded completely.

The Liszt that followed, of course, was breathtaking. In any hands, this Dante Sonata is a real monster, requiring all the skills that a pianist can possibly muster to bring it off. Not only did Shunta Morimoto succeed, but he appeared to bring a new dimension to the work by shaping the quieter sections so finely and so eloquently. Earlier in the day, I had listened to two other performances, by Paul Lewis and Alfred Brendel, so the work was already in my head. Shunta Morimoto’s rendition made me feel like I was hearing it for the first time, so surprising did I find his nuances of interpretation. It was totally recognisable, but totally new at the same time. What a performance!

After a wholly spontaneous standing ovation, he offered the Chopin Barcarole as a substantial encore. Shunta Morimoto, for sure, is a unique talent. He surely has a stellar career ahead of him, and richly deserved. Special.

Tuesday, November 5, 2024

Monday, October 28, 2024

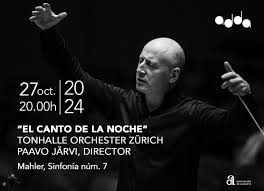

Mahler Seven by the Tonhalle Zurich under Paavo Jarvi in ADDA Alicante

A concert program that devotes 77 minutes to a single

work is not commonly encountered. Yes, there are the symphonies of Mahler and

Bruckner and Shostakovich, but what else would commonly occupy such a length of

time? It was with some excitement that this big event was anticipated.

The bill was, without question, up to the challenge. Zurich’s

Tonhalle Orchestra is certainly one of the world’s leading orchestras, and Paavo

Järvi’s name could not be bigger in the world of conducting. This particular Mahler

Symphony, number seven, is one that I last heard in live performance in a

concert over fifty years ago on London’s South Bank. So even the torrential

rain in Alicante that surrounded this evening could not damp the enthusiastic

anticipation.

Well, did the evening live up to the expectation? Of

course it did. The performance was faultless, even brilliant at times, even if

it could be argued the Paavo Järvi’s tempo in the faster sections of the first

movement could have been a little faster. The

overall impression, however, was that the contrasted were stark but never grotesque.

This is truly sophisticated music that almost constantly surprises the listener,

and it must be expertly played to make sense. The Tonhalle Orchestra took every

challenge in its substantial stride and in this variation-like movement, one

could not even hear the joins.

Mahler 7 is a groundbreaking symphony in many ways,

not least in its structure. A first movement that is alternatively fast and

then reflective lasts for 22 minutes. Its loose variation form revisits the

same material, but Mahler’s imagination keeps the sound fresh throughout, never

in the slightest repetitive. The central section of the movement, that

momentary vision of marital bliss, does eventually disintegrate to chaos.

The finale is Mahler perhaps at his most optimistic.

The movement seems to dance several waltzes along the way, but overall the

feeling is that everyone is having a good time, even though the dance may seem

to have a strange shape here and there.

The central scherzo is a very strange experience. Mahler

more often than not uses the scherzo to be loud, abrasive, even cynical. But in

the seventh, it seems more like a bad dream half-remembered. In between two movements,

entitled Night Music, it sounds as if the composer was trying to get to sleep, then

nodded off for a short time and dreamt, and then woke up before dawn to lie

awake again. The night music movements are perhaps stranger than the scherzo,

given their placement after a grand opening and before a triumph for

conclusion. Overall, Mahler’s seventh seems like an inverted arch, with a

keystone sticking up annoyingly in the middle to stop listeners from sliding

down or up.

On a thoroughly successful evening, when the concert

received rapturous applause from its audience, I find the need again to praise

the ADDA audience for being such wonderful listeners. It’s as if this audience

actually absorbs the music.

Saturday, October 19, 2024

Paquito D'Rivera and Aaron Copland under Jost Vicent in Adda, Alicante

He also told us that a friend told him a joke about an

elephant, and that led to the composition of the piece that opened the concert,

The Elephant and the Clown. This orchestral work lasts about eight minutes and

features an array of percussion and lines that might be described as jazz riffs

played by different sections of the orchestra, especially the strings. This is

upbeat, optimistic music, which presents a sophisticated, improvised style to

larger forces.

“The Journey”, Rice and Beans Concerto followed. This

was utterly original in that it featured a quintet of soloists, playing

percussion, piano, cello, harmonica and clarinet, the latter played by the

composer himself. This combo of soloists played in concerto fashion alongside

the orchestra in the piece that mixed Cuban rhythms with jazz, with classical

forms, with African influences, and even the sounds of Chinese music, since one

of the piece’s movements was inspired by a visit to a Chinese barrio in Havana.

Antonio Serrano played harmonica and Pepe Rivero piano. Yuvisney Aguilar

clearly had wonderful time on percussion, while Guillame Latil made light of an

incredibly demanding and significant cello part, originally played in the work’s

premiere by Yo-Yo Ma.

Overall, the three sections Beans, Rice, and The Journey

made a spectacular impression on the audience, with again apparent jazz riffs

regularly racing through the scoring. But this was not “light” music. There are

really challenging sounds in this score, and many quotational references, both thematically

and texturally to the concert hall repertoire of the twentieth century.

An encore was inevitable. Another short orchestral

piece by Paquito D’Rivera filled the bill perfectly. Personally, I have never

heard his music before this concert and this experience will surely have me thoroughly

explore his works.

The other half of the contrast, in theory, came in the

shape of the Symphony No. 3 of Aaron Copland. Could this be further from the

riffs and improvisatory style of the first half? Surely this is one of the twentieth

century’s major works…

And it was here that the stroke of Josep Vicent’s

artistic direction emerged, because repeatedly in this score Aaron Copeland

uses jazz like patterns in the strings. They are not as fast, not as

advertently virtuosic as those that Paquito D’Rivera had written, but they were

there. And, well, Paquito D’Rivera might be a Cuban, but he has spent much of

his artistic life in the USA, effectively importing an émigré style and

presenting it to an American audience. But we must remind ourselves that Aaron Copland’s family were themselves emigres from Russia. So this quintessentially

American music might just have its roots elsewhere!

Copland’s Third Symphony is itself an optimistic

affirmation of individuality. Just like jazz. And by the time the theme of The Fanfare

for the Common Man appeared in the last movement, having been regularly

suggested throughout the previous three, the effect is totally symphonic. The

music seems to grow, with an idea that is bigger than its own sound.

But it is never secure in its affirmation. Modal

harmonies see to that, always suggesting a major key, but always refusing to

forget the possibility of the minor. There is always somewhere else in mind.

Both Aaron Copland and Paquito D’Rivera remind us that we are all in the mix

together, influenced by many cultures and sharing the same world.

Shostakovich’s Waltz from the Jazz Suites came as an

encore. Its surreal use of a minor key for the dance’s main theme always

surprises. Paquito D’Rivera also felt a certain surprise when the second encore

offered Happy Birthday to him to celebrate his seventy years on stage.

Tuesday, October 1, 2024

Sunday, September 29, 2024

Ethan Frome by Edith Wharton

This is a masterpiece of story-telling. It is short - about 130 pages - and tells the tale of a man living an isolated life in New England. The time is not specific, but the feel is always contemporary with the date of publication, which was 1911. The narrator met Ethan Frome in Starkfield, Massachusetts and immediately his countenance made its impression. He is described as already looking “as if he was dead and in hell.” The narrator sets about telling the story of Ethan Frome, a story that apparently is hard to extract from the laconic people who inhabit this part of New England. The structure of the novel, we are told, reflects this local habit, but by the time we are half way through, the reticence seems to have eased.

Starkfield

is a harsh place. Winters are particularly difficult, and people measure

lifespan by the number of winters they have survived. This is not a sociable

community, we are told, and people live isolated lives. It is an isolation that

in some ways is dictated by their environment. “Beyond the orchard lay a field

or two, the boundaries lost under drifts; and above the fields, huddled against

the white immensities of land and sky, one of those lonely New England farmhouses

that make the landscape lonelier.” It is thus a place where the distance

between people renders everything lonelier.

Ethan

Frome has a sick wife. She needs a home help, live-in assistance. Mattie Silver

is hired. She is young, full of life and frankly not much of a help. She is a

relative of Ethan Frome’s wife, Zelda, and so is tolerated. Ethan is attracted.

Mattie changes his life.

What happens is so important to the story that how it happens cannot be described. Let it be said that what appears to be a simple love triangle does not turn out to be so. Though reticent, these people live charged emotional lives and conflict is never far removed from the cold.

Edith Wharton’s prose is wonderfully evocative of this

isolated and inward-looking community. In her fiction, she is generally an

urban creature, wandering the society events of New York, describing the nuances

of class politics among the well-to-do. The fact that in Ethan Frome she

inhabits a quite different environment with fundamentally different people

living different lives is testament to her skill as a writer.

Dialogues and Natural History of Religion by David Hume

As ever,

David Hume comes across as a logical positivist of the eighteenth century. For

him, it seems that there are three possible positions to take on any natural

phenomenon, belief or custom. First, something may be known. Where science has

trod, where theory has been discussed and where findings have been demonstrated

and then reproduced, Hume will admit no deviation of interpretation. Everything

else is folly. Secondly, something may be widely assumed but as yet it remains

unproven. Though he regularly alludes to such phenomena, he actually rarely

analyses consequences of taking a particular standpoint, or pronounces on

whether such things, perhaps at a later date, might become known. Throughout

his pronouncements on such topics, he reveals himself to be as unquestioning of

his assumed culture as anyone who espouses religion. An illustration of this

tendency would be his regular reference to “savages”, people who don’t really qualify as human beings. These beings tend to

live in Africa, in “jungles” or even in Asia. These are, of course, my own

tongue-in-cheek words. He does not question the labels he uses, or their

existence as such. But he repeats the position and clearly sees no reason to

question it, despite the fact that it is not a “known” fact, in terms of there

existing any kind of proof – or, for that matter, even evidence.

The third

category in Hume’s thought relates to things that are unknown. Not only do

these phenomena exist outside his concept of science in that they cannot be

tested, but also, they defy description in a way that human beings can

comprehend them. It is in this third category, the unknown, that human beings

find fertile ground for their pronouncements of religion.

What is

known is adequately described by this passage: “if the cause be

known only by the effect, we never ought to describe to it any qualities beyond

what our precise the requisite to produce the effect: nor can we, by any rules

of just reasoning, return back from the cause, and other effects from it, beyond

those by which alone it is known to us.” Here the process of scientific

inference is raised to the status of a rational god, perhaps. But it is

rational…

What is

assumed but not proven is illustrated by this assertion: “I

am sensible, that, according to the past experience of mankind, friendship is

the chief joy of human life, and moderation the only source of tranquility and

happiness. I never balance between the virtuous and the vicious course of life;

but I’m sensible, that, to a well-disposed

mind, every advantage is on the side of the former.” The assertion exists because he

believes it, and can cite evidence, but he does not have proof. But equally he does

not admit belief, believing that at some point the quality may be tested and

proven, perhaps.

What is

unknown, outside of human inference facilitated by a scientific method, then

becomes explained by speculation, or invention. Human beings hold up a mirror

to the universe, and in its see themselves and interpret phenomena beyond their

understanding as mere aspects of themselves. “…there is an

universal tendency among mankind to conceive all beings like themselves, and to

transfer to every object, those qualities with which they are familiar

acquainted, and of which they are intimately conscious. We find human faces in

the moon, arm is in the clouds; and buy a natural propensity, if not corrected

by experience and reflection, ascribe, malice, or goodwill to everything, that

hurts or pleases us. Hence the frequency and beauty of […] poetry; where trees,

mountains and streams are personified, and the inanimate parts of nature,

acquire sentiment and passion. although these poetical figures and expressions

gain not on the belief, they may serve, at least, to prove a certain tendency

in the imagination, without which they could neither be beautiful nor natural…

philosophers cannot entirely exempt themselves from this natural frailty, but

have often described it to inanimate matter the horror of a vacuum […] and

sympathies, and other affections of human nature. The absurdity is not less,

while we cast our eyes upwards; and transferring, as is to usual, human

passions, and infirmities to the deity, representing him as a jealous as

jealous and revengeful, capricious and partial, and, in short, a wicked and

foolish man, in every respect, but his superior power and authority.”

Personally,

I have often wondered why, given our knowledge of the universe and our place

within it, why the religious continue to use personal pronouns and human labels

to refer to gods. “He, Father, Lord” are common: “it” and “thing” are not. In a

reconstructed terminology, “The Lord is my Shepherd” would thus become “It is a

thing”. Without the completely human dimension, the phrase becomes meaningless.

With the human dimension raised to a status of essential, the phrase no longer

describes anything that might not be earth-bound.

Hume

expands on this elsewhere: “…the great source of our mistake in

this subject, and of the unbounded license of conjecture, which we indulge, is,

that we consider ourselves, as in the place of the Supreme Being, and conclude,

that he will, on every occasion, observe the same conduct […] in his situation,

would have embraced as reasonable and eligible. But, besides that the ordinary

course of nature may convince us that almost everything is regulated by

principles and maxims very different from ours, besides this, I say, it must

evidently appear contrary to all rules of analogy to reason, from the

intentions and projects of men, to those of Being so different, and so much

superior.” He also

equates the tendency to adopt religious believe to ignorance: “…it

seems certain, that, according to the natural progress of human thought, the

ignorant multitude must first entertain some groveling and familiar notion of

superior powers, before they stretch the conception to that perfect Being, will

be stowed order on the whole frame of nature.” He does however admit that there are possibilities for

the committed: “A little philosophy, says Lord Bacon, makes men atheists: a

great deal reconciles them to religion.”

Dialogues and Natural History of Religion are a superb illustration of what

drove David Hume towards his eighteenth-century version of logical positivism.

They come here with copious notes, where the numerous classical illusions are

clarified, and where the author’s references to contemporary writers and texts,

now forgotten, are referenced.

The Children Act by Ian McEwan

Ian McEwan’s novel The Children Act is probably as close to the label masterpiece as any piece of fiction might get. Having just read David Hume’s ideas on religion, where the all-powerful takes on a human face, where rational thought is raised the status of an ivory tower, and where human prejudice regularly masquerades as potentially rational opinion, this novel provided a perfect fit to counterbalance and contextualise continued thought about these fundamental issues.

The novel

immediately introduces Fiona. She is married, her adopted surname of Maye

appearing sometime later. She is a judge. She has risen to a significant

pinnacle within her profession. Married to Jack, for who knows how long, she

shares a relationship which is both childless and lately unsteady, largely

because Fiona’s work seems to take

over her life.

She is

very thorough. The law requires judgments to be correct, justifiable within the

confines of the law, itself, especially in the UK according to precedent, but

they must also at least approach the concept of natural justice, in that they

must at least appear to be morally as well as legally justifiable. The process

of reconciling these two demands often results in conflict. Complication arises

when the subject of the legal action is a child, because, when that child is

below the age of majority, eighteen years of age, the child is not deemed

mature or responsibly enough to make up its own mind.

Fiona

specializes in cases involving children. These may be to determine custody

after divorce, protection against a malevolent parent or merely an absent one.

They may involve a care order, where a child is judged to need the safety or

stability of institutional care when parents are abusive, drug addicted,

negligent, alcoholic, or merely absent. The issues may be fairly clear, but

nothing is more complicated than human relationships. And even when these are

simple, we seek to complicate them. But when seventeen-year-old is the subject of

legal action, the situation is more complex. Especially when religion has

reared its complicated head…

Adam has leukaemia

and needs a blood transfusion. Without it, his chances of survival are limited

because the drugs that form half of his treatment only work if a transfusion is

carried out. Alan, like his parents, however, is a Jehovah’s

Witness, to whom blood transfusions are anathema, simply not allowed. The

question for Fiona to judge upon is whether the child can refuse treatment,

whether his parents are denying him a chance of life for ideological reasons

and whether the professionals involved should countermand the parents’ and the

patient’s wishes. Fiona decides to visit Adam in hospital to inform her

position. This happens against the backdrop of her own marriage failing, her husband

walking out and an approaching eighteenth birthday for Adam, meaning that then

he will be able to decide for himself what happens. She finds Adam interesting.

Adam finds Fiona slightly more than captivating.

What happens is the book’s plot, and a reader will

just have to discover it by reading the book. What I can write to conclude my

review is the fact that these issues of the correctness or rationality or

otherwise of belief come into sharp focus when ideology becomes a life and

death issue. And Ian McEwan deals with these issues in a highly complex and

transparent manner, which is also highly creative. What will always be dilemmas

without resolution are presented as such, but somehow, they are never

complicated. Decisions taken always seem justified by circumstance. What people

do scene by scene makes sense, but then overall everything is driven by the

moment, by assumption and by personal identity that we cannot control, because

it grows within us, apparently independently. Fiona approaches every situation

with a judge’s eye for the law, with an eye for accuracy and correctness.

Internally, she reveals herself as vulnerable, open to instinctive and

irrational thoughts.

What Ian McEwan does is portray character supremely

well, providing a balance between the professional, the personal, and the

social elements that contribute to make a human being. David Hume’s quote from

Bacon really does ring true, that when we become really involved in the issue,

then the case for religion strengthens. As for Fiona, life must go on. But how?

ADDA Alicante under Josep Vicent begin a new season with Bruckner's Seventh Symphony

Anton Bruckner was born in 1824, meaning this year is his bicentenary. In recognition of this, the new season of Alicante concerts opened with a performance of his Seventh Symphony by the ADDA orchestra under the artistic director, Josep Vicent.

This is a mammoth work that lasts over an hour. The first two movements alone exceeded forty minutes. As a result, as with this evening, it is often played alone, with no other work either before or after it to offer musical contrast. With such immersion, an audience ought to feel bathed in the musical style to such an extent that the experience is all enveloping.

But nothing involving Anton Buckner is ever that that simple. He was a paradoxically simple man, yet simultaneously outrageously complex. Deeply religious, but with an often-expressed passion – unrealised - for young girls, he seemed to offer up to the world a riddle that could never be solved. A professor in Vienna and a teacher of many years, he never attained sufficient confidence in his own abilities to finish definitively most of his works. Near constant revision, often prompted by the lukewarm praise of others, left multiple versions of many of his works. This can give much scope for conductors to pick and choose, to incorporate this revision or ignore another. Definitive Bruckner is an oxymoron.

And with the work of Anton Bruckner, no one is going to notice very much, given that by design the music often swerves, changes direction or delights in apparent non sequiturs quite often. Bulow described the composer as “half genius, half simpleton” and he had the reputation, even in society events, of turning up dressed like a peasant. He was an enigma, was overtly sensuous with the sound of his music, but deeply religious, and lived, generally speaking, the life of an ascetic. His express motivation was to write music to celebrate the glory of God, in both scale and depth.

The ADDA programme notes quoted Wilhelm Furtwangler saying that Bruckner composed Gothic music that had mistakenly been transplanted into the nineteenth century. Stylistically, the music is far from Gothic, but perhaps its architecture is not. Personally, I would go as far as describing the symphonies as cathedrals, where the parts only come together when the whole is considered from afar. There are no grab quotes from these symphonies, except perhaps in the scherzi, and even these are heavy on process rather than melody.

A possible problem with the cathedral analogy is perhaps that the composer had forgotten to include a door. It is possible to experience this music and feel permanently shut out. Yes, the edifice is impressive. Yes, it towers above us. But does it ever reveal its interior?

Having discussed the work, what about the performance? Well, it was faultless, committed, subtle, and even communicative. The Wagner tubas did not play a wrong note all evening, which is rarely the case with this notoriously mind-of-its-own instrument. Their sound, booming and enveloping, when added to a full orchestra created a special world, which the audience eagerly inhabited.

Josep Vicent drew every morsel of texture from the score

and the resulting detail, even within the tutti, was simply vivid. In

recognition of the work’s dedication to Ludwig II of Bavaria. The concert bore

the subtitle “Legend of the mad king”. It wasn’t a legend, but it was a great

start to a new season.

Monday, September 16, 2024

The Stories of Eva Luna by Isabel Allende

In The Stories of Eva Luna, Isabel Allende presents a

collection of stories ostensibly told by Ralph Carlé’s partner. Ralph is a

television journalist and features in the last story of the set when he tries

to free a young girl trapped by mud after a landslide.

Before the prologue in which Ralph Carlé asks to be

told stories, Isabel Allende refers to Sheherezade of Arabian Nights fame. Her

task was to keep the Grand Vizier entertained all night until dawn so that she

might survive the telling, unlike all who had previously been similarly tasked.

A footnote informs the reader that Sheherezade did indeed succeed in her quest.

“At this moment in her story, Sheherezade saw the first light of dawn, and

discreetly fell silent.” This surely implies that a woman with a gift of

language might just escape the nightly attentions of a man. Such attentions

feature large throughout the The Stories of Eva Luna and all the usual and

perhaps inevitable consequences follow to form the central focus of almost

every one of these tales.

These stories are written in the magical realism style

of much Latin American fiction. The language is quite dense, but often not as

dense as the fusillade of events that attach themselves to the lives of these people

in this provincial, quiet and often rather boring town. The lives described in

the stories, however, are surely never dull. Indeed, so full of detail are they

that these short stories would be difficult to digest as suggested over a

single night.

Try, for instance, this passage about an English

couple. “The large headquarters of Sheepbreeders Ltd rose up from the sterile

plane like a forgotten cake; it was surrounded by an absurd lawn and defended

against the depredations of the climate by the superintendent’s wife, who could

not resign herself to live outside the heart of the British Empire and continued

to dress for solitary dinners with her husband, a phlegmatic gentleman buried

beneath his pride in obsolete traditions.” There are many who might understand

something general in this particular description.

I read these stories in a first English paperback

edition, and, it has to be said, there were several misprints. When reading

magical realism, however, one is never sure if the misprint might just have

been intended. On board ship, for instance, Maria just might have been

interested in her desk. “Several days after the tragedy, Maria emerged with

unsteady step to take the air on the desk for the first time. It was a warm

night, and an unsettling odour of seaweed, shellfish, and sunken ships rose

from the ocean, entered her nostrils, and raced through her veins with the

effort of an earthquake. She found herself staring at the horizon, her mind a

blank and her skin tingling from her heels to the back of her neck, when she

heard an insistent whistle; she half-turned and beheld two decks below a dark

shadow in the moonlight, signalling into her.”

Local politics aften figures large in the stories.

There are corrupt local officials, some honest ones, dictators called

benefactors and revolutions, bandits and thieves. There is even a man who

maintains his respectability by virtue of the existence of buried gold which,

when push comes to shove, is no longer where he put it.

A theme that reemerges several times is the eventual

payback by a woman badly treated, misused or merely abused. Some of the twists

and turns of plot, nay of lives, are too unexpected to have been imagined. Many

of these events would have probably been true, but perhaps not so vividly

embroidered. In fact, some of these tales are so densely woven that a reader

might want a rest here or there! But they are superb and no doubt better if

read in Spanish.

The She-Apostle by Glyn Redworth is a tale of self-harm,

ideological control, and international terrorism. In the late sixteenth and early

seventeenth century, when the book is set, the social medium within which the

self-harm of especially young women was perpetrated was the Church. The

ideological control in question was also perpetrated by the Church, a control

so absolute, misguided and complete that individuals often suffered

hallucination as a result of the guilt that was heaped upon them by what they

were taught. International terrorism, in the case of The She-Apostle, is

manifest in the Gunpowder Plot, when a group of ideologically driven fanatics

tried to blow up the entire political leadership of a sovereign state, being

England under James the First. If this were a review of a contemporary novel,

the fact that it featured self-harm promoted by social media, hallucinations

and violence, and international terrorism might be merely par for the course.

When, as is the case of Glyn Redworth’s book, it is associated with the life of

a seventeenth century saint, it may seem strange. It might just be that little

has changed in human society in the intervening four hundred years, except, of

course, our appreciation of just how brutal life was at that time.

Doña Luisa de Carvajal y Mendoza was born in Extremadura

into a Spanish nobility that was enjoying the country’s Golden Age. Colonies

overseas were disgorging their riches towards the seat of imperial power, the

nobility were gobbling up the proceeds and Spanish priests were at work, saving

the souls of a whole continent by converting them to Christianity, whilst at

the same time sending them to heaven at the double by infecting them with

smallpox, influenza, and typhoid. Europe was riven by ideological differences

between Catholics and Protestants that to an outsider seem about as

consequential as disagreeing about how many angels would fit on a pinhead. If

you are a Christian, I accept, angels matter. If you are not, they don’t exist. The evidence, surely, lies on that side, but

whenever did the ideologically committed ever trouble themselves with evidence?

Unless, of course, it could be twisted into a case against someone who thought

differently from oneself…

Born with several silver spoons already in her mouth,

Luisa sought solace in faith. She was regularly abused by her guardian, in the

name of God, of course, and regularly harmed herself with instruments of

torture. Eventually, she adopted a life of frugality, continued to self-harm,

and to pioneer a life of religious devotion that was personal rather than

institutionalized. She never became a nun. She also decided to free the English

from the manacles of Protestantism and, soon after the armada had failed to do the

same by force, moved to England to follow her mission.

Glyn Redworth’s The She-Apostle is more than a

biography of Luisa. It perhaps stops short of being a conventional hagiography.

The author does describe the personal and societal consequences of Luisa’s

campaign to promote Roman Catholicism in Protestant England, but quite often a

reader might feel that the author stopped short of delivering the criticisms of

her actions that he himself felt. Luisa may indeed have sought martyrdom, but

her crime in the end was to steal the remains of already butchered Roman

Catholics, put to death by a state that arrogated absolute power because of the

terrorism they threatened.

As a reminder, it must be pointed out that the method

of choice by which the just imposed their will on dissenters was as follows. “Hung,

drawn and quartered” might sound like it might apply to a Spanish ham. But in

that age, it meant being hung by the neck until you are almost dead. Then you

were cut down and disembowelled, your intestines being trailed onto a fire as

you watched. Then your arms, legs and head were cut off and then the final

ignominy was that your torso was cut into quarters, each part of you destined

for a different resting place. The idea, of course, was ideologically driven in

that admission to heaven needed intact remains, so once quartered, a person was

to be damned forever.

Louisa, herself, was indeed arrested for stealing the

remains of executed Catholics, although she herself died eventually in bed. She

wanted to pass on the dried-out flesh and bones of the martyred as relics to

consecrate holy places. But she was spared the ignominy of the gallows and axe

so there was no obvious martyrdom for her. Glyn Redworth’s book, though

superficially adulatory, does give a vivid portrayal of the political and

social life of the time, and as such it is worth reading. For a believer, I

suppose it provides joyous example of a pious life. For a nonbeliever, like me,

it portrays the shockingly violent absurdity of the irrational.

Tuesday, August 27, 2024

Aaron’s Rod by D H Lawrence

Aaron’s Rod by DH Lawrence is a perplexing novel. It seems to represent two quite different aspects of the writer’s creativity. One side has him reflecting on working class life in the English midlands, whilst in the other he is very much the sophisticated traveller and philosopher. These apparently reflect his own origins and reality. The book’s duality is not surprising, when one considers the fact that the early part of the book dates from 1918 and represents an abandoned project. Only three years later did Lawrence return to the work and write the second, more substantial part.

First, the title needs interpretation. Aaron’s Rod, historically, refers to the sacred staff carried by the brother of Moses. It was Aaron who persuaded the flock to worship the golden calf. The rod was used as both symbol of office, and as a means of summoning spiritual power. In the novel, the term is used to refer to the flute which is played competently and professionally by the principal character, Aaron Sisson. Frankly, and in keeping with Lawrence’s preoccupations, it is also a sexual reference to the character’s maleness.

The first part of the book describes Aaron Sisson’s background, upbringing an early life. Thus, rooted in a working-class English midlands mining town at the turn of the twentieth century, Aaron’s aptitude for music makes him stand out, makes him at least seem to have rebelliousness in him. He marries locally. Children come. Love goes. Perhaps desire dies not, however, as this passage illustrates. “…sometimes when she put down her knitting, or took it up again from the bench beside him, her fingers just touched his thigh, and the fine electricity ran over his body, as if he were a cat tingling at a caress.” He leaves his wife and his home area to travel first to London, then to Italy.

It is in London that he meets Lilly. Lilly is the surname of a man, Rowan Lilly. The character features large throughout the rest of the book and might be seen as expressing some of the writers own ideas. He starts by nursing Aaron and back to health after an illness and then departs on his travels. On his invitation, Aaron follows, despite not having much money. On arrival, he finds that his friend Lilly has absented himself.

Life in London had been interesting, both professionally and socially. Aaron pursued his music and even found time and funds to go to the opera. His working-class origins allowed him to make fun of the audience. “Not being fashionable, they were in the box when the overture began…” As a musician, he explores music that such fashionable audiences might shun. There is evidence that Lawrence intended thus to place Aaron on the outside of ‘middle-class society’. When he is asked, later on, about his musical preferences, Aaron expresses his liking for Mussorgsky’s Khovanshchina, which at time of the book’s writing had received only one London production.

Eventually, Aaron ends up in Florence, where the book really comes to life. Aaron is befriended by an upper-class family, and he meets a countess, who has a suppressed love of music. They make music together, without any really real commitment from either of them, except to their individual needs. Having regained contact with Lilly, Aaron and a group of acquaintances analyse their lives, their estrangement from wives they no longer love, from a past that the Great War has seemed to render irrelevant and estranged.

Eventually, an anarchist’s bomb destroys the front of a café where Aaron is seated, taking out the front windows and destroying the coat rack at the entrance., His flute was in the pocket of the coat and is ruined. Aaron himself survives. But what is he now? He is both penniless and his source of employment is destroyed. Where can a man go when his rod is taken from him?

It is the almost constant reference to the effects of the Great War that is the enduring impression of the novel. Unlike many writers, Lawrence does not appear to take sides. He is probably against war, per se, but he does not slip into a common trap of identifying those who benefited from the conflict and contrasting them with those whose lives were destroyed. For Lawrence, it seems, everyone has suffered. War only destroys, as do all acts of violence, as does the final act of violence, perpetrated for political ends. It achieves only destruction. War also changes social relations, as evidence by the passage “…what should you like to drink? Wine? Chianti? Or white wine? Or beer?” The old-fashioned “sir” was dropped. It’s too old-fashioned now, since the war.”

A reader starting Aaron’s Rod must bear in mind that the book’s opening chapters do not reflect where it will take you. Eventually, it is a thoroughly challenging and complete experience for the reader. Its enduring message that the only things that drive human existence are love and power is itself powerful. It is a complex relationship, however, between the two, because to seek love is often to exert power, and that power can often be controlled, but can also be associated with violence, which is only destructive. It is, say several of the characters, a power exerted primarily by women.

Alps and Sanctuaries of Piedmont and the Canton Ticino by Samuel Butler

In Alps and Sanctuary Samuel Butler walks various alpine passes, visits many small towns and villages, comments on art and architecture, and drinks considerable amounts of wine. The author wrote this travel book in 1882, but this was not an account of a single stay in the region. On the contrary, Samuel Butler regularly makes it clear throughout the text that he is referring to his previous visits to many of the places on his itinerary. He thus records changes in the fabric of the buildings, transformations in the lifestyles of the inhabitants and sometimes refers to memories of those previous trips. This makes the text much more than a simple description of a journey.

But Samuel Butler, like many British authors abroad, cannot resist the occasional pontification. Many of these positions entail the assertion of Protestantism above Catholicism, and here and there the reader can almost feel the author biting his tongue so as not to cause disagreement with an acquaintance.

And what about this for someone who, on the face of it, observes and seeks explanation of natural phenomena? “Reasonable people will look with distrust upon too much reason. The foundations of action lie deeper than reason can reach. They rest on faith – for there is no absolutely certain incontrovertible premise which can be laid by man, any more than there is an investment for money or security in the daily affairs of life, which is absolutely unimpeachable. The funds are not absolutely safe; a volcano might break out under the Bank of England. A railway journey is not absolutely safe; one person, at least, in several millions gets killed. We invest our money upon faith mainly. We choose our doctor upon faith, for how little independent judgment can we form concerning his capacity? We choose schools for our children chiefly upon faith. The most important things a man that has are his body, his soul, and his money. It is generally better for him to commit these interests to the care of others of whom he can know little, rather than be his own medical man, or invest his money on his own judgment, and this is nothing else that making a faith which lies deeper than reason can reach, the basis of our action in those respects which touches most nearly.”

Unlike many authors, Samuel Butler regularly alludes to music to provide background, impression, explanation and quality to the experience describes. These are always fully notated and could cause many readers to panic. The author simply assumes that all his readers also read music. In 1882, it might have been true of his largely middle-class readers, who probably had been taught to play the piano from the age of five.

Samuel Butler makes no excuses for his conservatism, nor for his no doubt sincere Christian faith. But for the modern reader, the consequences of his belief structure, formed around the assumptions of Victorian England, might be perceived as stuffy, bigoted or even racist. For instance, he criticizes natural phenomenon phenomena when they refuse to conform to human preconceptions. Birds, for instance, know not one iota of public-school discipline. “People say the nightingale’s song is so beautiful; I am ashamed to own it, but I do not like it. It does not use the diatonic scale. A bird should either make a no attempt to sing in tune, or it should succeed in doing so. Larks are Wordsworth, and as for canaries, I would almost sooner hear a pig having its nose, ringed or the grinding of an axe. Cuckoos are all right; they sing in tune. Rooks are lovely, they do not pretend to tune. Seagulls again, and the plaintiff creatures that pity themselves on moorlands, as the plover and the curlew, or the birds that lift up their voices and cry at eventide when there is an eager air blowing upon the mountains and the last yellow in the sky is fading – I have no words with which to praise the music of these people.”

But it seems that in the 19th century, there already existed British tourists who find themselves less than appreciated at destination, because they take their assumptions with them. In one place, “…there was an old English gentleman at the hotel Riposo who told us that there had been another such festa not many weeks previously, and that he had seen one drunken man there – an Englishman – who kept abusing all he saw and crying out, ‘Manchester is the place for me’.” Samuel Butler largely did the same.

But if anyone chooses to dismiss such procedural niceties of the

nineteenth century as old-fashioned nonsense, spare a thought for the fifteenth

century inhabitants of the monastery at S. Michele who had to follow the

dictates upon their work issued by their boss. These can be found at length in

Appendix II of Butler’s work.

.jpeg)