Wednesday, November 27, 2024

Saturday, November 16, 2024

Helsinki Philharmonic under Saraste play a Sibelius programme

Jukka-Pekka Saraste conducted the Helsinki Philharmonic orchestra in a program devoted to the music of Sibelius. Now a Finnish conductor with a Finnish orchestra playing Finnish music might sound like it could turn out to be a cliché. But these people know precisely what they are doing with their national composer. Clearly, the Helsinki Orchestra plays a lot of Sibelius, but they also clearly never tire of the task.

The concert started with a work not published in the program. The previous concert had been cancelled in the aftermath of the devastating floods that had hit the Valencian region. As a mark of respect for those who have suffered, the orchestra opened with the Valse Triste of Sibelius. It was a gesture appreciated by the audience.

The first half of the concert then got underway with Jan Söderblom, the Helsinki Philharmonic leader playing the First Serenade for violin and orchestra, Opus 69a. This is a thoroughly understated work. The Second Serenade, more substantial and more musically interesting came third on the program with Jan Söderblom again as soloist.

In between, the orchestra’s principal flute, Niamh McKenna, was soloist in the Nocturne No.3 from Sibelius’s incidental music to Belshazzar’s Feast. So it was with these three short pieces, featuring solo violin, flute, and then violin again that the concert started. If I have a criticism, which I accept is the level of nitpicking, I would suggest that these three pieces should have been presented with the flute first or last, allowing the two serenades to be played back-to-back. It was in this form that the Helsinki orchestra premiered in 1915, a concert which also featured the original version of the fifth symphony.

The performance of Finlandia that followed saw several extra musicians take to the stage and the familiar cords did ring out. Finlandia is a thoroughly moving experience and no matter how many times it is played, it always has a rousing effect on an audience. This was no exception.

The second half was taken with a performance of the Fifth Symphony, though in its revised version, not the original of 1915, which is never now played. And the fifth is perhaps the composer’s most popular work, alongside the Violin Concerto. With such a well-known work, it would be easy to fall into the trap of mouthing platitudes, but this performance was anything but that. The music was fresh, as fresh as Sibelius himself would have wanted when he said that whereas modern composers were offering up cocktails, he only wanted fresh spring water. The music was both clear and refreshing.

There was also an encore, the Alla Marcha from the Karelia, which needed even more musicians on stage

Friday, November 8, 2024

Shunta Morimoto at the Denia International Piano Festival in Bach, Chopin and Liszt

I don’t normally write detailed reviews of chamber music concerts. It’s not because they often aren’t memorable, it’s just that I tend to go to so many of them, it’s often hard to keep up with the writing! This lack of motivation to put pen paper is especially marked when the repertoire on offer is very much standard, comprising often performed works that frankly I have heard many times. It’s not that familiarity breeds contempt. It’s just that what does one say about another fairly standard performance of a standard work, albeit that both the work and the performance are superb? Nearly all the performances I have heard over the years are wholly competent, with one or two exceptions, but it becomes hard to say anything new about them. So what is it about a concert that featured J. S. Bach’s French Suite No. 6 BWV 817, Chopin’s Opus 28 Preludes and Liszt’s Dante Sonata that has provoked me to write? Answer: the performer and the performance. Both were outstanding.

Shunta Morimoto is a young Japanese pianist. He was 19 when he won the Concurso de Piano Gonzalo Soriano in Alicante in April 2024. The competition is organized by Ars Alta Cultural in conjunction with Conservatorio Profesional de Música, Guitarrista José Tomás and this year there were over 100 entrants, with half of them competing in level D, the section for adults, whose age rage was from 18 to 32. Shunta Morimoto, therefore, was at the younger end of the range, and he was the youngest of the finalists. I have been listening to music intently for about 60 years. But I knew from the moment Shunta Morimoto depressed a key in that room in April that he would win the competition and, furthermore, that I was about to witness something wholly special. Put simply, Shunta Morimoto is a genius.

Part of the prize for winning the Gonzalo Soriano competition was to appear in the Ars Alta Cultural concert series in Denia at the end of 2024 and that concert, part of the Denia International Piano Festival, was last night. Shunta Morimoto offered the program mentioned above and, for perhaps the first time in thousands of concerts and recitals that I have attended, I can report that not one of the 110 or so people in the audience made a single sound, apart from applause, of course, throughout the one and a half hours of music. There was no interval, but amongst the audience, silence ruled, so utterly wrapt was everyone in what they heard.

It is hard to describe in words what is so compelling about this young man’s playing. The moment you hear the music, it is obvious, but written words have to be read, not heard. Many pianists use bravura, strength and volume to impress. Many play as fast as possible. Shunta Morimoto can offer bravura, the spectacular and the speedy. But above all what he can do is communicate via the music and it is this speaking, apparently directly to an audience without the need of words that is utterly captivating, even arresting.

Every phrase of every piece he played last night was shaped, thought through to make musical sense. At times, he played so softly the music was barely audible, but every note was there, every gesture was clear, every phrase fit perfectly with the musical argument he presented. Even the silences he interspersed for effect were listened to intently by a thoroughly captivated audience.

Chopin’s Opus 28 Preludes, perhaps, was never intended to be played as a single work. But in the right hands, even a composer’s lack of vision can be straightened. I am reminded of a performance about 30 years ago when Murray McLachlan played all the Etudes of Chopin end to end, Opus 25 followed by Opus 10. He was clear that it would not the other way round. I have never forgotten that performance on a baby grand Kawai in a Brunei Hotel. Last night, Shunta Morimoto knew that the Opus 28 Preludes could be played as a single work, and he was right. He succeeded completely.

The Liszt that followed, of course, was breathtaking. In any hands, this Dante Sonata is a real monster, requiring all the skills that a pianist can possibly muster to bring it off. Not only did Shunta Morimoto succeed, but he appeared to bring a new dimension to the work by shaping the quieter sections so finely and so eloquently. Earlier in the day, I had listened to two other performances, by Paul Lewis and Alfred Brendel, so the work was already in my head. Shunta Morimoto’s rendition made me feel like I was hearing it for the first time, so surprising did I find his nuances of interpretation. It was totally recognisable, but totally new at the same time. What a performance!

After a wholly spontaneous standing ovation, he offered the Chopin Barcarole as a substantial encore. Shunta Morimoto, for sure, is a unique talent. He surely has a stellar career ahead of him, and richly deserved. Special.

Tuesday, November 5, 2024

Monday, October 28, 2024

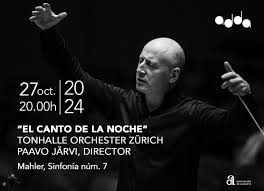

Mahler Seven by the Tonhalle Zurich under Paavo Jarvi in ADDA Alicante

A concert program that devotes 77 minutes to a single

work is not commonly encountered. Yes, there are the symphonies of Mahler and

Bruckner and Shostakovich, but what else would commonly occupy such a length of

time? It was with some excitement that this big event was anticipated.

The bill was, without question, up to the challenge. Zurich’s

Tonhalle Orchestra is certainly one of the world’s leading orchestras, and Paavo

Järvi’s name could not be bigger in the world of conducting. This particular Mahler

Symphony, number seven, is one that I last heard in live performance in a

concert over fifty years ago on London’s South Bank. So even the torrential

rain in Alicante that surrounded this evening could not damp the enthusiastic

anticipation.

Well, did the evening live up to the expectation? Of

course it did. The performance was faultless, even brilliant at times, even if

it could be argued the Paavo Järvi’s tempo in the faster sections of the first

movement could have been a little faster. The

overall impression, however, was that the contrasted were stark but never grotesque.

This is truly sophisticated music that almost constantly surprises the listener,

and it must be expertly played to make sense. The Tonhalle Orchestra took every

challenge in its substantial stride and in this variation-like movement, one

could not even hear the joins.

Mahler 7 is a groundbreaking symphony in many ways,

not least in its structure. A first movement that is alternatively fast and

then reflective lasts for 22 minutes. Its loose variation form revisits the

same material, but Mahler’s imagination keeps the sound fresh throughout, never

in the slightest repetitive. The central section of the movement, that

momentary vision of marital bliss, does eventually disintegrate to chaos.

The finale is Mahler perhaps at his most optimistic.

The movement seems to dance several waltzes along the way, but overall the

feeling is that everyone is having a good time, even though the dance may seem

to have a strange shape here and there.

The central scherzo is a very strange experience. Mahler

more often than not uses the scherzo to be loud, abrasive, even cynical. But in

the seventh, it seems more like a bad dream half-remembered. In between two movements,

entitled Night Music, it sounds as if the composer was trying to get to sleep, then

nodded off for a short time and dreamt, and then woke up before dawn to lie

awake again. The night music movements are perhaps stranger than the scherzo,

given their placement after a grand opening and before a triumph for

conclusion. Overall, Mahler’s seventh seems like an inverted arch, with a

keystone sticking up annoyingly in the middle to stop listeners from sliding

down or up.

On a thoroughly successful evening, when the concert

received rapturous applause from its audience, I find the need again to praise

the ADDA audience for being such wonderful listeners. It’s as if this audience

actually absorbs the music.

Saturday, October 19, 2024

Paquito D'Rivera and Aaron Copland under Jost Vicent in Adda, Alicante

He also told us that a friend told him a joke about an

elephant, and that led to the composition of the piece that opened the concert,

The Elephant and the Clown. This orchestral work lasts about eight minutes and

features an array of percussion and lines that might be described as jazz riffs

played by different sections of the orchestra, especially the strings. This is

upbeat, optimistic music, which presents a sophisticated, improvised style to

larger forces.

“The Journey”, Rice and Beans Concerto followed. This

was utterly original in that it featured a quintet of soloists, playing

percussion, piano, cello, harmonica and clarinet, the latter played by the

composer himself. This combo of soloists played in concerto fashion alongside

the orchestra in the piece that mixed Cuban rhythms with jazz, with classical

forms, with African influences, and even the sounds of Chinese music, since one

of the piece’s movements was inspired by a visit to a Chinese barrio in Havana.

Antonio Serrano played harmonica and Pepe Rivero piano. Yuvisney Aguilar

clearly had wonderful time on percussion, while Guillame Latil made light of an

incredibly demanding and significant cello part, originally played in the work’s

premiere by Yo-Yo Ma.

Overall, the three sections Beans, Rice, and The Journey

made a spectacular impression on the audience, with again apparent jazz riffs

regularly racing through the scoring. But this was not “light” music. There are

really challenging sounds in this score, and many quotational references, both thematically

and texturally to the concert hall repertoire of the twentieth century.

An encore was inevitable. Another short orchestral

piece by Paquito D’Rivera filled the bill perfectly. Personally, I have never

heard his music before this concert and this experience will surely have me thoroughly

explore his works.

The other half of the contrast, in theory, came in the

shape of the Symphony No. 3 of Aaron Copland. Could this be further from the

riffs and improvisatory style of the first half? Surely this is one of the twentieth

century’s major works…

And it was here that the stroke of Josep Vicent’s

artistic direction emerged, because repeatedly in this score Aaron Copeland

uses jazz like patterns in the strings. They are not as fast, not as

advertently virtuosic as those that Paquito D’Rivera had written, but they were

there. And, well, Paquito D’Rivera might be a Cuban, but he has spent much of

his artistic life in the USA, effectively importing an émigré style and

presenting it to an American audience. But we must remind ourselves that Aaron Copland’s family were themselves emigres from Russia. So this quintessentially

American music might just have its roots elsewhere!

Copland’s Third Symphony is itself an optimistic

affirmation of individuality. Just like jazz. And by the time the theme of The Fanfare

for the Common Man appeared in the last movement, having been regularly

suggested throughout the previous three, the effect is totally symphonic. The

music seems to grow, with an idea that is bigger than its own sound.

But it is never secure in its affirmation. Modal

harmonies see to that, always suggesting a major key, but always refusing to

forget the possibility of the minor. There is always somewhere else in mind.

Both Aaron Copland and Paquito D’Rivera remind us that we are all in the mix

together, influenced by many cultures and sharing the same world.

Shostakovich’s Waltz from the Jazz Suites came as an

encore. Its surreal use of a minor key for the dance’s main theme always

surprises. Paquito D’Rivera also felt a certain surprise when the second encore

offered Happy Birthday to him to celebrate his seventy years on stage.