On the face of it, Walker appears to be a rather conventional young man. He does not seem to be particularly ambitious. He is not assertive, and rarely takes the lead. He is not driven by urges to succeed, dominate or enrich himself. But he does not seem to form relationships easily, though neither does he obviously shun them. There always seems to be something in the way.

He does become interested in the personal histories of down-and-outs who sleep rough on the streets of the cities he inhabits. He is interested in them as individuals, concerned to know where they come from, and how they managed to finish up poor and destitute. He does find some common threads, and these form an essential element of the book’s plot.

Walker himself is a veteran of the final battles of World War II. He participated in the D-day landings and suffers regular flashbacks to the experience of being on a Normandy beach without cover and being shot at. He lost many comrades in battle and seems constantly to ask what gave him the right to survive. Perhaps this enduring trauma of war is what repeatedly denies him the self-confidence, self-awareness or perhaps ambition to participate in life, except as an almost detached observer. It is also the aspect of life that denies him a means to share the lives of those around him. He seems cocooned in a past that haunts him and controls the way he relates to others.

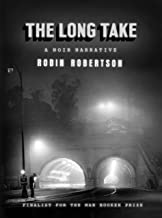

I have deliberately chosen not to mention The Long Take’s most obvious characteristic before describing its content, because questions of form can often dominate when they do not deserve to take pride of place. But now it is time to state that Robin Robertson’s novel, The Long Take, is written in verse, and this makes it rather unusual. Now as with all verse, the act of reading it is a rather different experience from reading prose. There is a necessary and inevitable need to pause, to absorb words, to observe lines and to identify the flow of rhythm. And it is via this use of verse that the author also more finally tunes the reader’s moments of complete concentration on and dedication to the text. What works extremely well in this scenario is the focus on the details of Walker’s experience, both in his current life and on those beaches during wartime, whose memories endure. The Long Take often tingles with a reality that can also sting. Walker’s regular flashbacks are also indicated typographically, appearing in italics to give them the stress that the reader thereafter subconsciously assumes.

What does not work well is the characterization

associated with the books protagonists. If this were a film, then most

characters other than Walker would probably appear rather as no more than

cameos. But this is a small criticism, because the enhanced emotion offered by

the verse more than compensates for any lack of descriptive context. The Long

Take cannot be read quickly. It's a verse form demands the reader’s

concentration and commitment. It is, however, a rewarding experience and

eventually an intensely moving book, describing lives destroyed by the continued

experience, as well as the historical reality and unseen consequences of war.