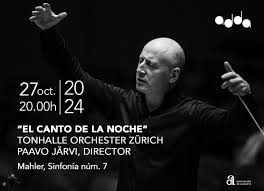

A concert program that devotes 77 minutes to a single

work is not commonly encountered. Yes, there are the symphonies of Mahler and

Bruckner and Shostakovich, but what else would commonly occupy such a length of

time? It was with some excitement that this big event was anticipated.

The bill was, without question, up to the challenge. Zurich’s

Tonhalle Orchestra is certainly one of the world’s leading orchestras, and Paavo

Järvi’s name could not be bigger in the world of conducting. This particular Mahler

Symphony, number seven, is one that I last heard in live performance in a

concert over fifty years ago on London’s South Bank. So even the torrential

rain in Alicante that surrounded this evening could not damp the enthusiastic

anticipation.

Well, did the evening live up to the expectation? Of

course it did. The performance was faultless, even brilliant at times, even if

it could be argued the Paavo Järvi’s tempo in the faster sections of the first

movement could have been a little faster. The

overall impression, however, was that the contrasted were stark but never grotesque.

This is truly sophisticated music that almost constantly surprises the listener,

and it must be expertly played to make sense. The Tonhalle Orchestra took every

challenge in its substantial stride and in this variation-like movement, one

could not even hear the joins.

Mahler 7 is a groundbreaking symphony in many ways,

not least in its structure. A first movement that is alternatively fast and

then reflective lasts for 22 minutes. Its loose variation form revisits the

same material, but Mahler’s imagination keeps the sound fresh throughout, never

in the slightest repetitive. The central section of the movement, that

momentary vision of marital bliss, does eventually disintegrate to chaos.

The finale is Mahler perhaps at his most optimistic.

The movement seems to dance several waltzes along the way, but overall the

feeling is that everyone is having a good time, even though the dance may seem

to have a strange shape here and there.

The central scherzo is a very strange experience. Mahler

more often than not uses the scherzo to be loud, abrasive, even cynical. But in

the seventh, it seems more like a bad dream half-remembered. In between two movements,

entitled Night Music, it sounds as if the composer was trying to get to sleep, then

nodded off for a short time and dreamt, and then woke up before dawn to lie

awake again. The night music movements are perhaps stranger than the scherzo,

given their placement after a grand opening and before a triumph for

conclusion. Overall, Mahler’s seventh seems like an inverted arch, with a

keystone sticking up annoyingly in the middle to stop listeners from sliding

down or up.

On a thoroughly successful evening, when the concert

received rapturous applause from its audience, I find the need again to praise

the ADDA audience for being such wonderful listeners. It’s as if this audience

actually absorbs the music.

No comments:

Post a Comment